Friday, August 9, 2019

0

Friday, August 9, 2019

Samuel Albert

Read more...

The Abenguni (AbaNgoni of Nyasaland)

The Genealogy of their Chiefs.

Lunyanda

Magangati

1. Mlotshwa 2. Mafu

Mbekwane

1. Zwangendaba 2. Ntabeni 3. Mgayi

Mbelwa (Mombela) 2 Mpezeni (first born, not heir), 3.Mthwalo, 4. Mphelembe 5 Maulawu (Sons of Zwangendaba)

The AbeNguni of Nyasaland migrated from Natal at the time of the disturbances of Tshaka. They had travelled southward from up-country as had the AmaXhosa, but they turned again and, retracing their steps, went north.

I have given them a place in this book because I believe they are one in origin with the Xhosas. Their name AbeNguni also decides me. As of old the name represents the tribe, and the tribe originates from some Chief whose name it bears.

It was not by accident that the Xhosas were described as Abenguni. The appellation is derived from an ancient chief of the tribe called Mnguni.

With regard to this point, Mr Fuze in his book, entitled, The Black Races (Abantu Abamnyama), says of the AmaXhosa, "The major portion of the tribe of the Chief Mnguni went westward toward the setting sun....It is the same Mnguni who was father of Xhosa, who, it would seem, was the great son of Mnguni. This tribe (AmaXhosa) has been long separated from their relatives whom they left behind (p.78). The point raised by this son of Zulu, we have referred to before. Its repetition is meant to draw attention especially to the latter part of Mr Fuze's statement. He says in brief: "The Xhosas in removing from the North (from Dedesi) left behind them a remnant of their own people, the AbeNguni in Natal."

Now we find that the people who responded to that name are the AbeNguni of Zwangendaba, and moreover the the tribe was known by that name in Natal prior to their migration northward. Evidence to this effect is found in the statements of Ntombazi, mother of Zwide.

In order to understand the point it ought to be borne in mind that Zwangendaba, Chief of the AbeNguni, had gone with his people to live under the protection of Zwide, the Chief of the AmaNdwandwe tribe.

The AmaNdwandwe were at constant war with Tshaka, often defeating him by the help of the AbeNguni. There came a day when the AmaNdwandwe were also defeated by Tshaka, whereupon Zwide withdrew with Zwangendaba to the country now described as Wakkerstrom.

There a quarrel arose between Zwide and Zwangendaba which was decided by the assegai. Zwide was defeated and made a prisoner by Zwangendaba, but after a time the latter relented, mindful of their former relations, when they fought their numerous battles together, and he released Zwide sending him home with provisions in the shape of sleek cattle.

But it would seem this act of kindness did not pacify Zwide. The scandal of his defeat embittered him, and he vowed vengeance on Zwangendaba.

The missionary of the AbeNguni in Nyasaland, Doctor Elmslie, says in his book on the history of these people:- Zwangendaba, who was one of the chief captains of Zwide, although living under Zwide, was not subject to his authority altogether.

After his quarrel with Zwide that Chief marshalled his forces seeking to revenge himself on Zwangendaba. When Zwide's impi was assembled at the Royal Kraal preparatory to marching out against Zwangendaba, Ntombazi, wife of Langa and Zwide's mother appeared and endeavoured to discontinuance the war, saying to her son "My child, would you destroy the AbeNguni? Did they not release you and send you home with many sleek cattle?"

But Zwide was not to be appeased. Upon which, Ntombazi adopted a singular course in order to remove this thought from her son's mind. In full view of the assembled host she disrobed herself and stood before them completely naked. This most unusual action startled and disconcerted the warriors who, filled with traditional superstition, regarded it as an omen of impending disaster; they were unmanned and disheartened and refused to fight.

Now for my present argument, the important point is this:- Ntombazi described the people of Zwangendaba as the AbeNguni. That was at that time quite a familiar name, nor was it casually adopted, nor yet was it given to them by other tribes like the Tongas who only heard their name in their flight northward from Shaka.

There are those who say: This name of AbeNguni originated with the Tongas when Sotshangana (Manukuza) arrived among them, fleeing from Tshaka. But Manukuza was a son of Gasa of Zwide's tribe, the AmaNdwandwe.

In seeking a new country he proceeded along the seaboard and settled in the territory beyond the Limpompo River which is now described as the country of Gasa (Gasaland). Gasa was a younger brother of Zwide.

Others again say: The tribe of Manukuza got their name from the Tongas who called them Abenguni because, as they said, the name implied that they were thieves or bandits. My reply is that Manukuza was one of the Ndwandwe tribe, which was only politically related to the tribe of Zwangendaba.

Manukuza tribe are not AbeNguni. True, in former days they were neighbours, assisting each other in their wars, but differing in tribal origin. It is reasonable to infer, therefore, that because of the familiarity of the name it also came to include the people of Manukuza. To the Tongas the name AbeNguni may be familiarly connected with thieving, but other tribes do not use in that sense. Here the tribal title is taken from a person who originated the tribe namely Mnguni.

We left Zwangendaba on unfriendly terms with Zwide, and it appeared to this son of Mbekwane that in the circumstances his present abode would not, to use a Xhosa expression, "rear him any calves." In other words, he determined to leave Zwide and look for a new country in which to settle.

At that time, these chiefs and their peoples were settled in the Wakkerstrom district, just north of Natal, where they had proved a hard nut for Tshaka to crack.

Departing thence, Zwangendaba took the road to Mzilikazi's country, with whom he was on friendly terms, and who had preceded him in his flight to the country now known as the Transvaal and settled there. He followed the coastline at a distance, then went further into the interior looking toward the setting of the sun. Arrived at Mzilikazi's place they lived on friendly terms, but only for a time.

Therefore, Zwangendaba trekked, this time turning towards the sea in search of his friends Manukuza and Mhlabawadabuka, sons of Gasa, youngest son of Langa, son of Ndwandwe. He cleared a road with the assegai, sweeping, his enemies before him, and none could stay him in his course.

He arrived there with with his following enlarged by accessions from other tribes he defeated in his course. However he did not stay long with Manukuza, for trouble arose between Manukuza and his younger brother, Mhlabawadabuka, and the latter was driven away. The latter with his following then joined Zwangendaba.

Now, people who have been accustomed to rule by the assegai and to live independently, do not easily accommodate themselves to the rule of others, which becomes irksome to them. So they separated from Manukuza, Zwangendaba while his "feet were still wet" (with travelling) parted from Manukuza together with Manukuza's younger brother, Mhlabawadabuka, making for the North.

Smaller parties broke off from them on the way up; some settled at the Sabi, others at the Zambesi. In the year 1835, Zwangendaba crossed the Zambesi near the township of Zumbo, built on the shores of the Zambezi by the Portuguese.

He forced his way until he crossed the Tshambezi, a river which precipitates itself into the Lake Bangweolo, and skirting the shores of Tanganyika entered the country of the AmaFipa. The AbeNguni of Zwangendaba having reached this country settled there, and took possession of the land for themselves.

But this tribe was still to break into two sections. Zwangendaba, whose language was outspoken and who, besides being a man of power, was loved and respected by his people, at length lost his vitality, being well on in years when he arrived among the Fipa, and he died there. He left several sons.

The sections which broke away from the AbeNguni after Zwangendaba's arrival there, were numerous. The most notable were the AmaTuta, AmaViti, AmaLavi and the AmaHehe. These tribes exercised authority over all the country north of the Zambesi and right up to Tanganyika.

There were few tribes which dared to fight with them. Inorder to understand the strength of these tribes, we must remember that the Amasai, a tribe of Hamitic origin responsible for the migration of Bantu tribes from their country at the Tana, and was powerful enough to settle among other tribes of the Bantu, is described by Mr Last as follows : "The Masai are reported to be the most powerful of the races of Central Africa, but should they ever meet the AmaHehe in a life and death struggle there would be wonders and surprises and a reshuffling of tribes, for it is not the first time the Masai have been beaten by the AmaHehe."

This tribe settled below the Ruaha, a branch of the Rufigi (A.H. Keane, Africa, Vol. II., p. 512) The AmaHehe (WaHehe) tribe in September 1891 routed a large force of Germans. It is a very savage tribe, and is a terror to any of the surrounding tribes.

And so it was with the AbeNguni, they have the capacity to live. They also know how to die like men.

Let us now follow the sections which went out from the AbeNguni of Zwangendaba, and set up tribes of their own. We have already seen that Zwangendaba died in the land of the AmaFipa, also termed the AmaSukuma. After his death, internal disputes over the succession arose and frequent battles followed. Mgayi, a younger brother of Zwangendaba, broke away with other followers, and went forth till he came to the neighbourhood of the great lake, the Victoria Nyanza. The country did not suit him, so he returned to the place where his elder brother died - the territory of the AmaSukuma.

There Mgayi died, and as successor Mpezeni, eldest son by birth of Zwangendaba, was appointed chief. But he was not the heir although the first born. Mpezeni did not satisfy the abeNguni by his administration and they deposed him, substituting Mbelwa (Mombela) who became Zwangendaba's heir in his place. So Mpezeni removed with his following, and created his own tribe.

Thursday, August 8, 2019

0

Thursday, August 8, 2019

Samuel Albert

Read more...

Last Battle of the AmaNdwandwe with the Help of Zwangendaba's Ngoni

Source : The South-Eastern Bantu, Abe-Nguni, Aba-mbo, Ama-Lala by John Henderson soga

Dingiswayo, for whom Tshaka professed great affection, was killed in a war with the AmaNdwandwe of Zwide. This tribe had often fought with Tshaka and had frequently beaten him. It was the most powerful of all the tribes that refused to become tributary to the ImiThethwa.

Dingiswayo, for whom Tshaka professed great affection, was killed in a war with the AmaNdwandwe of Zwide. This tribe had often fought with Tshaka and had frequently beaten him. It was the most powerful of all the tribes that refused to become tributary to the ImiThethwa.

Tshaka, the unconquerable, had in the death of his chief found a pretext for another trial of strength with his great rival. He spoke disrepectfully of Zwide, of Ntombazi, Zwide's mother, and of Langa, Zwide's father, expecting that his expressions of contempt would be carried to the Ndwandwe chief, and his expectations were realised.

Two men of importance in Tshaka's service, Ngqwangube and Nikizwayo, were under sentence of death, and fled to Zwide. These men reported Tshaka's words to the Ndwandwe chief who sent back the following message, "Son of my old friend, why do you revile me so? Fix your spears in their shafts. I am coming."

The Ndwandwe army took the field shortly after this warning. Its immediate objective was the headquarters of Tshaka at the Gqori hills, where Tshaka had two depots of troops, namely Mbelembele and Sirebe.

The Ndwandwe warriors were commanded by Noluju, Zwide's general. When he came in sight of the Gqori, Noluju arranged his warriors in two divisions. One division he sent against the Mbelembele, and the other against the Sirebe. The Zulus were likewise formed up in two divisions, each defending its own headquarters.

Ngqengelele, son of Vulana was commander-in-chief of Tshaka's forces. As Zwide's warriors came on to the attack, Tshaka surrounded by his bodyguard, all bearing black shields, took up a position to view the battle.

Fighting against the Mbelembele, Zwide drove in the right wing of Tshaka's force, while at the same time Zwide's right wing was driven back by the Zulus. Exactly the same thing happened at Sirebeni.

When Tshaka observed that his army was in danger of being cut to pieces, he grew restive and demanded that his shield, black and white in colour, should be handed to him by his bearer, intending personally to lead his men.

The regiments forming his bodyguard he divided and sent one body in support of his right wing at Mbelembele which was badly shaken, the other he sent against the left wing of Zwide's warriors who were threatening to break through his right wing at Sirebeni.

These arrived just in time to avert disaster and, taking advantage of the check imposed on Zwide's forces, succeeded in carrying out an encircling movement, and thus at both points had the enemy at a great disadvantage.

Desperate fighting followed, and for a long time the issue hung in the balance, but in the end, after a sanguinary contest , the Ndwandwes broke through the encircling Zulus, but only to retreat.

The victory was so decisive that Zwide with the whole Ndwandwe tribe made preparations to evacuate their old country. This decision they carried out and moved right up to the Wakkenstroom district from the sea-board near St Lucia lake.

Part of Zwide's army was composed of Zwangendaba's AbeNguni, who later separated from Zwide and went north. These are the AbeNguni or AbaNgoni, of Nyasaland, and are, as has been stated at the end of the part of this book dealing with the AmaXhosa, to be of the same stock as the latter.

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

0

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

Samuel Albert

Read more...

Shaka Zulu's Cruelty and His Demise

Source : The South-Eastern Bantu, Abe-Nguni, Aba-mbo, Ama-Lala by John Henderson soga

Perhaps the wars in which Tshaka engaged as supreme chief of the Imithethwa and AmaZulu reveal the best side of the man, or at least do not display conspicuously the evil that was in him.

Perhaps the wars in which Tshaka engaged as supreme chief of the Imithethwa and AmaZulu reveal the best side of the man, or at least do not display conspicuously the evil that was in him.

His warrior and their leaders by their excesses help to share any responsibility, and to keep his shortcomings in the background. The savage nature of this inhuman tyrant comes into clearer relief through the details of his private life.

In a fit of ungovernable fury over some trivial matter, he stabbed his mother, Nandi, to death, and afterwards made a great show of extreme grief. Mr Henry Fynn states that the Zulus told him that Nandi died from dysentry.

But A. M. Fuze (in Abantu Abamnyama) in reference to this says, "Is it likely that the Zulus would open their hearts to a whiteman on the real facts of a matter of this kind?" Which, in short, means that Tshaka actually killed his mother with his own hands.

There are so many instances of his extreme brutality that it would require a separate volume to record them all. We therefore pass them over and refer to the last, which so exasperated everyone that the natural corollary was the determination to put him to death.

The Zulu army had been despatched on an expedition against the Pondos. Though they overpowered the Pondos, the Zulus were yet unable to follow them into the fastness of the Mgazi and completely crush them. So, having exacted a promise from them that they would become tributary to Tshaka, the Zulus contented themselves with this and the captured cattle and returned home.

In the absence of his army on this expedition, Tshaka professed to have had certain revelations made to him, through the medium of dreams. He summoned the wives of many of the absent warriors before him. He, then, went through the formulae of the witch-doctor, and charged each one with being guilty of a certain offence.

Each individual was asked, "are you guilty?" When the answer was "No," the unfortunate woman was put to death. Others, hoping to escape the same fate, would reply "Yes," but they also were put to death.

Thus he trifled with the lives of human beings, disregarded the sacred ties of human affection. The tiger had tasted blood. It is said that four hundred of the wives of his warriors were done to death by him on this occasion.

Having temporarily satiated his lust for blood, he began to think and, in thinking, to fear the effect of his excesses on the army. Consequently on its return, he allowed it no time to rest, but sent it immediately on another expedition, this time far to the north-east.

That the death of Tshaka was being privately canvassed is evident from an incident which took place about this time. It is related that a notorious thief, Gcugcwa, was brought before Tshaka. It should be mentioned that certain forms of theft were punishable by death. This man was of the AmaQwabe tribe, that is, the Principle House of the Zulus, and was therefore a relative to the tyrant, and of some standing by birth.

When he appeared before Tshaka, the latter said to him as if in salutation, Sakubona Gcugcwa ("I see you, Gcugcwa"). Gcugcwa replied, "Yes, Ndabezitha, I see you also." A second time Tshaka said, Sakubona Gcugcwa. The culprit saw a veiled menace in the salutation, but replied as before.

The Qwabe thief was no coward, and feared not death. When Tshaka, therefore, a third time said to him Sakubona Gcugcwa, Gcugcwa replied "Yes chief, you see me to-day, but others will see you to-morrow." "Seize him," said the chief, and Gcugcwa was led to instant execution.

Retribution is a slow traveller, but reaches its destination in the end. The principal conspirators working for the death of Tshaka were his two brothers, Dingana and Mhlangana. They had not, as is sometimes stated, gone out with the army on its expedition to the north-east, but had on some pretext remained at home.

They got into touch with Tshaka's immediate personal attendant, Mbopha, son of Sithayi, and succeeded in gaining him over to their interest by promising him a large tract of Zululand, and recognition as chief of that part of the country.

Dazzled by this offer he became a tool in their hands. A sister of Senzangakhona, Tshaka's father, named Mkabayi, was still alive. She had seen her two nephews, Nomkayimba and Mfogazi, cruelly put to death and their inheritance seized by Tshaka.

She never forgave him and carried an aching heart with her through life. The conspirators knew this and broached the subject to her. She gave them every encouragement and used all her influence and powers of persuasion to detach Mbopha from his allegiance to Tshaka, and with the help of the promises made to him by Dingana and Mhlangana succeeded. Mbopha dissembled before his master till the fatal day arrived.

Tshaka was engaged with Faku's representatives who had come to tender the submission of the Pondos as tributary to the Zulu chief, at the same time placing before him the cranes' feathers, and other articles demanded as an indication of their submission. The meeting was in progress within the cattle kraal of the Great Place.

Tshaka seemed to be dissatisfied with the tribute, and was remonstrating with the Pondos, when Mbopha entered, followed by Dingana and Mhlangana. Mbopha took advantage of the chief's attention being distracted to plunge his assegai into Tshaka. Dingana and Mhlangana also set upon him, stabbing him repeatedly till he died. The Zulus thus sacrificed one tyrant, but in Dingana they got another and, if possible, a worse one.

|

| Dingane kaSenzangakhona |

Monday, May 6, 2019

0

Monday, May 6, 2019

Samuel Albert

Read more...

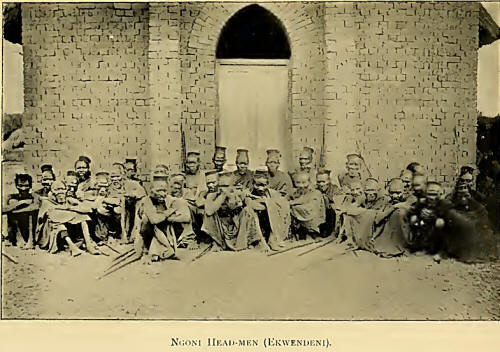

Livingstonia Mission Meeting With Ngoni Headmen 1890s

Among the Wild Ngoni

Chapter VI. Meeting with the Head-men

A WEEK after our visit to Mombera a messenger arrived to say, that next day we were requested to come and repeat our words to the head-men of the tribe. We had heard various rumours in the interval, which had caused us no little anxiety as to what would be the result of the meeting. It was said that I had come with many loads of calico, beads, brass wire, and all the many things the Ngoni desire, and at the meeting I was to enrich the people and make them great. Great was the excitement of the people over this piece of news. How such an idea came to them takes us back to the first meeting of Dr Laws with them, when the subject of war was referred to. Dr Laws had said that by obeying “the Book” and giving up war and plunder, they would become richer and greater than they were. The spiritual sense in which the statement was made was not perceived by the Ngoni, and from that day many were the theories expressed of how “the Book” was to bring riches and greatness to them. The native lives only for the present and could not be expected to see the force of such a statement, but it served to emphasise the special work we, unlike trading Arabs who were the only foreigners they had seen, had come to do. We were “the people of the Book” and not for trade. The Book was talked of, near and far, and became a source of wonder and enquiry, so that even from the start, while no systematic mission work was allowed, not a day passed on which some information was not given and seed sown, which, as we now view our work, has borne good fruit. It was no uncommon occurrence to see a group of strangers from a distance, at the house with the request to be shown the Book,—they had heard of it and wished to see it.

On the morning of the great council of ama-duna we were in the chiefs cattle kraal at eight o’clock, and the whole day till three o’clock in the afternoon was occupied in talking. The cattle-fold is the centre of every Ngoni village. At the royal kraal, where we met, it was a circular space about eighty yards in diameter fenced with young trees. Around it in ever widening circles the huts of the people were built. The gate was at the side nearest the river, and at the opposite side was a smaller gate leading from the chiefs quarters, which were fenced off from the houses of the ordinary people. In the centre of the cattle-fold there was one of the huge ant-hills which are so numerous throughout Ngoniland.

Soon after our arrival, troops of warriors fully armed marched in and took up their situations in the enclosure. There were eventually several hundreds present, but perfect order and quiet were observed. When all the warriors had assembled, the chief councillor, Ng’onomo, and the others came in. There were eleven present that day. Accompanying the councillors was a large number of men of inferior rank but possessing certain powers in the tribe. The councillors seated themselves in a semi-circle near to us. After the usual delay each saluted the Mission party, and then Mr Koyi rose to open the business. They were told I had come desiring to stay among them, and to teach them the Word of God, and to heal the sick. Several of the councillors spoke, and all were very warm in their expressions of welcome and readiness to give permission to my staying. All went smoothly until Ng’onomo got to his feet. He began by performing a war-dance, which, being accompanied by the war-shouts of the warriors present, and as I could not understand its meaning, discomfited me not a little. I was reassured when I caught the broad smile on Sutherland’s face as he looked at me.

All the nice bits of native politeness and flattery had been said, and Ng’onomo, bent on the one question of war and conquest, desired to give the meeting a more practical turn. He finished his war-dance, and after recapitulating the speeches of the others, he plainly said that they were not to give up war; that they were accustomed from their infancy to take the things of others and could not see any reason why they should change their habits. He said, “The foundation of the kingdom is the spear and shield. God has given you the Book and cloth, and has given to us the shield and spear, and each must live in his own way.” To emphasise this utterance, he again danced. We had adopted the plan of replying to anything said when the speaker sat down. Mr Koyi replied, saying that the Book was given to all mankind, and that as we were all the children of God it teaches us that we ought to live in peace with each other. Here I may say that there is no word in Ngoni for “peace.” They now use an imported term,—their own expression which comes nearest the idea being “to visit one another.”

No new question was raised at that time, but two crucial matters with the Ngoni in those days were brought up. They had been brought up when Dr Laws met the council, and for many a day constituted posers for us. One was the flight of the Tonga to Bandawe, and the other was their desire to have the exclusive right to the presence of the white men in the country. Mr James Stewart in 1879 visited Mombera, and wrote thus—“The next day, Saturday, we reached Mombera; but when I enquired for the chief, I was told he was ‘not at home.’ It was soon evident that he was either designedly absent, or that he simply denied himself. We saw only inferior head-men, who expressed dissatisfaction that we had not come to settle among them, and that they did not understand why we should visit other chiefs before doing so. I have no doubt that they were sincere in their desire to make friendship with us; but an exclusive alliance would only suit them. We heard that they were tired of waiting for us, and intended now to take their own way, which, I fear, means war before long. They have lost both power and prestige within the last two years, and may now be resolving to regain both. I heard later that there are two parties in their council. Mombera and Chipatula and their head-men are desirous of peace and to invite us still to come among them, while Mtwaro and Mperembe wish to keep us at a distance, and to recover their power by force of arms.”

Ng’onomo asked what I was to do to bring back their former slaves, the Tonga, who had revolted and carried away some of their wives and children, their war-songs, and their war-dances. So long, he said, as we would not restore these, so long must they war to bring them and all other surrounding tribes into subjection, and if I would not in a peaceful way bring back the Tonga people, they would do so by war or drive them into the Lake. It required not a little caution to answer this statement, so as to still the excitement of the crowd of people present by whom such words were applauded. I directed Mr Koyi to say that no doubt they had many questions in which they were deeply interested, but as I had only just come among them, it was scarcely fair to demand of me a means of settling them before I had become acquainted with them and had learned their language.

My remarks had the effect of drawing a very sensible speech from an old councillor. He said I was only now like a child, unable to speak or walk, and as they did not call upon their children to go out to seek strayed cattle, or give judgments in the affairs of the tribe, so they should not call on me to settle their great matters while I yet eould not speak or walk. That statement turned the discussion into more favourable lines, and although the other question of leaving the Tonga and Bandawe and settling among the Ngoni exclusively was brought up, we were able to satisfy the people without exciting their jealousies, or agreeing to take sides with them against their runaway slaves. Ng’onomo afterwards returned to the war question, and endeavoured to show that their war raids on other people were not a bad thing. He said they were surrounded by people whom he called slaves, and that it was not their desire to kill them, but they endeavoured merely to chase them into the mountains, and when their food and flocks were secured, to say to them, “ Come down now and let us all live together.” It was conquest and not murder they pursued, as they could not bear the idea that any people should point the finger at them, and say, “X” (a click, expressive of contempt). He made an original proposal which was not less impossible for me to carry out. If we would agree to countenance one more raid on the people at the north end who were rich in cattle, and would pray to our God that they might be successful, they would, on their return, give us part of the spoil in cattle and wives, and would proclaim that the Book was to be accepted by the whole tribe. Here there was no place for parrying, and the reply was given emphatically enough that we were not the framers of the words in the Book, but merely the teachers charged to tell all men the words which were God’s and binding on us as well as on them, and that when God said, “Thou shalt not steal,” “Thou shalt not kill,” we had no power to change the command, and could not in any way countenance their wars. Then Ng’onomo asked if we would shut the Book and not pray against them if they went out. I said I had come to teach these words and could not but do so.

An interesting statement was made by one old man. He had evidently watched the life and character of Koyi and Sutherland, and considered its bearing on the practical things of daily life. He began by saying they were glad I was a doctor, and hoped I had medicine to make Mombera live long. He went on to speak of other medicine which he thought we possessed of which they had no knowledge. He said, “We see you white people are not afraid to go about all over the country, and you settle among different tribes and become the friends of all. How is that?

You have medicine (natives think everything is done by medicine as charms) for quieting people’s hearts so that they do not kill you. We cannot do so. We are not even at peace among ourselves. We speak fair words to each other, but that is not how we feel. We have also noticed that your servants are ‘biddable,’ and when ordered to do anything at once do it. It is not so with ours. We tell a slave to do a thing, and he says, ‘Yes, master, I have heard’; but he does not do it unless he chooses. We hope you will give us medicine to make our slaves obedient, and to quiet our enemies.” A better opportunity there could not have been for giving them a little plain instruction, and for putting in a word for schools which had been proscribed since the Mission began. Koyi, whose speech was as clear and pointed as theirs, made good use of his opportunity. He told them we had no medicine in their sense, but the words of the Book were stronger than medicine when taken to heart. He quoted the golden rule, and said, “That’s the medicine for quieting enemies everywhere, and was that which made all tribes the friends of the white men.” Then as to making servants obedient, h.e said the Book had words for both servants and masters. It told servants to be obedient and honour their masters; and masters to be kind to and patient with their servants, and give them their due in all things. He added that our servants were obedient and happy because they were being taught the Word of God, and because they were not our slaves, but were paid their wages regularly. He advised them to try it among theirs, and it would have the same happy results. Then he attacked once more the stubbornness of the people in refusing to allow schools. He said in doing so they were refusing the medicine which they were crying out for. As a native only could, he ridiculed them, and by happy and forcible illustrations made them hesitate in the position they held in refusing to allow schools. He said, “You are like a sick man in distress, who sees others being cured and cries for the same medicine, but refuses it when offered.” One replied by saying, “If we give you our children to teach, your words will steal their hearts; they will grow up cowards, and refuse to fight for us when we are old; and knowing more than we do, they will despise us.” That was met by saying that the Book had a command for children which they must allow to be good, viz., “Honour thy father and thy mother.” They would not be taught anything wrong, for all men are taught to fear God and honour the King. The school question was not discussed further; but no doubt some good was done, and the solution hastened by what had passed, although it was, as we shall see, two years after this ere liberty was given to open schools.

One other point it was necessary to refer to, as only the district immediately under Mombera was open to the Mission, so I requested leave to go about the country, as my desire was to help all. The districts of Mtwaro, Mperembe, and Maurau, brothers of the chief, were closed to us, not more by the hostility of these sub-chiefs, than by the jealousy of Mombera and his advisers, who desired to have the white men all to themselves, no doubt in view of the riches which were expected to come through them.

I was advised to stay with the others, as all were not favourable to our presence in the country; and while we would be guarded if in their midst, they could not tell what might happen if we went beyond Mombera’s own district into that of any of his brothers. This was not satisfactory, and as it was probably from jealousy, we pushed for liberty to go about. It was denied by the councillors, who repeated their reasons.

It was, however, clear in all that was said, that the real object of our presence among them was made manifest. However mistaken their ideas were as to the teaching of the Book, we were understood to be men with a message to be received, and they were honest enough to say they did not want it. No advance on previous liberties was made, but our position as neither wishing to bear rule over them nor to work for their overthrow, but to teach the Word of God, was made plain once more.

Then came the not very agreeable business of presenting the gift which we had taken for the councillors. There was considerable excitement visible generally, as each was presented with twelve yards of red cloth, a kind much valued by the head-men. As each had his portion presented to him there was an ominous silence for a time, and then a burst of derisive laughter. Some turned it over on the ground as if afraid to handle it. Some got up and measured it. One man took his and flung it among the crowd of warriors. One came over and said he did not want cloth. One only had the grace to thank me. They were reminded that we could not attempt to enrich them with goods, but had merely, according to their custom, brought “something in our hand” as a visible token of the friendship our hearts desired. One replied saying they saw we were not bent on enriching them, but it was good to remember that they had great hunger for various kinds of cloth and beads, and another day perhaps they would receive more. If I had come among them expecting the grace and politeness of civilization, instead of their proud indifference and sovereign contempt for the offering of friendship, my feelings would have suffered more than they did, but I was heartily glad when they rose up to go, and that the wild rumours of their expectations which we had heard for some days, found no more pronounced substantiation than their contemptuous treatment of what I thought was a sufficient gift for the purpose in view. The armed warriors, who appeared to have come as the bodyguard of the head-men, quietly filed out of the kraal and we were left alone.

Mombera was not present, and the councillors went to his hut to report to him the matters which had been talked over. Mr Koyi was called, and it seems the chief had enquired the reason why war dancing had been engaged in. He was angry at Ng’onomo and told him that the object of the gathering was not to discuss tribal matters with me, but to hear what I had to say. After a little the rest of us were called into the chiefs hut, where Ng’onomo and some of the other councillors were being regaled with beef and beer. The stiffness and formalities of the kraal meeting were absent, and no disappointment was visible. Mombera delivered a long speech bidding me welcome among them, and expressing joy that I was skilled in medicine. He himself was often sick, he said, and doubtless I had noticed that there were few old men present that day, the reason being that they were all dead, and if I could give them long life it would be good. He did not say how many never reached old age because they were killed in battle. If there were any doubts as to the full security of our position in the tribe, they were accentuated when Mombera repeated the warning of the councillors, that I should settle along with the others and not go into other districts. No doubt there was some desire to have exclusive possession of the white men, but it was noteworthy that although word had been sent to all the sub-chiefs to come to the palaver none had come, and none of their head-men were present.

With too great eagerness, perhaps, I pressed for permission to visit his brother, Mtwaro, at Ekwendeni, saying my desire was to become acquainted with all in the tribe and be of use to all. He and Mtwaro were not on friendly terms at that time, but as Mtwaro was heir-apparent it seemed advisable for the permanence of our work, in the event of Mombera’s death, to become known to Mtwaro and his head-men. Not since 1879, when Mr John Moir visited Mtwaro and had opened the way for others by friendly dealings with him, had anyone communicated with that sub-chief, and he had only once visited the Mission station. His armies were known to be out towards the Lake very frequently, and we all thought an attempt should be made to gain Mtwaro’s influence as Mombera’s had been gained.

After my statement had been interpreted to Mombera and he had consulted with some of those in the hut, he gave permission to visit Mtwaro and was thanked. He seemed to think that that would soften my heart, and so he plied his begging and his demands for cloth, beads, brass wire, big guns, little guns, gunpowder, dogs, bulls to improve his breed of cattle, needles, thread, and, above all, an iron box, with lock and key, in which to keep his valuables, which he said his wives and his councillors were in the habit of stealing. He said he would come over to see me when I could give him these things. It was hard to take all in good part and be at ease under his gaze over the beer-pot, and gracefully excuse our non-compliance with his overwhelming demands. Nothing but a desire to be a means of blessing to such a chief and tribe, would prove an inducement to live the life and experience which may be said to have begun that day. Forgetting the things not agreeable to flesh and blood, we soon after took our departure, feeling that some advance had been made in the work which we had come to take part in.

It was one advantage having to deal with a council rather than a single individual, and be continually subject to his capricious mind. As the Ngoni had a settled council who were not without dignity and caution in their deliberations, it was evident they had reciprocated our words as far as they could, as, not being over-anxious to allow us all we asked, they were prepared to make good all they allowed. The occasion was very similar to that on which Augustine came to Ethelbert as the first papal missionary to Britain. When he sent word on landing that “ he had come with the best of all messages, and that if he would accept it he would ensure for himself an everlasting kingdom,” Ethelbert would not commit himself, but answered with caution. When at last a meeting was convened, and Augustine “had preached to him the Word of life,” as Bede says, Ethelbert replied, “Fair words and promises are these; but seeing they are new and doubtful, I cannot give in to them, and give up what I and all the English race have so long observed.” But unlike Augustine, who was accorded the privilege of bringing any one of the people over to the new faith, we were told that the chief and council would first have to be taught, and if they considered our message safe, they would give us full liberty to teach the people.

It may here be noted how different has been the introduction of the Mission to all the other peoples in Livingstonia. In all the other districts the missionaries were hailed as the friends and protectors of the people. All were subject to stronger tribes, by whom they were constantly harried, or were trying to maintain an independent existence surrounded by their enemies; hence they gladly welcomed the missionary, hoping that his presence would prove their safety from their enemies. In no single case did they welcome him on account of his message; and the trouble in those early days was that he was pestered for medicine, guns and powder to kill their enemies. The Missions in those districts had the preparatory work to do in making the people understand the reason for their presence, just as we had of another kind in Ngoniland. Through the faithful testimony of Messrs Koyi and Sutherland, the Ngoni had by the time of my arrival come to understand clearly what our message really was. They needed not our protection from their enemies, as they were masters of the country for many miles around; and, indeed, their pride would not have allowed them to think that in any way a white man or two could be of any profit to them. They knew our teaching would strike at their sins of uncleanness, lying, war, murder and stealing, and they were, unlike the so-called deceitful, vacillating African, at least honest in their treatment of our words. There was great good in having got their ear so far; and even distinct refusal was far better than ready compliance, to be as readily retracted when occasion arose. It is far better to have to deal with an opposing council of head-men with power than with a chief himself, even although he agrees at the time.

If before leaving home I received one bit of advice more often than any other from Dr Laws, who had experience, along with Mr James Stewart and Mr Koyi, of the dangerous and trying work of gaining an opening among the Ngoni, it was that I should proceed gently and push nothing beyond what was a wise point. On such occasions as the meeting referred to, the judgment and caution of Mr Koyi were invaluable, and he was of opinion that we should not endanger our position with Mombera at that stage, while not sure that we would be received by Mtwaro. We sent a reply that we had no desire to act contrary to the chief’s wishes in the matter, and that until he could send someone to introduce us to his brother, we would refrain from going. It must be remembered that we were merely in the country on sufferance at that time. We did not even own the site of our house, and were not by any means assured of a permanent residence among them, so that we would not have been acting wisely had we been more anxious to assert our independence, than to improve the, as yet, slight hold we had on Mombera and his councillors. There are three special qualifications necessary in every missionary, viz., grace, gumption, and go. Prayer and the exercise of it will ensure the first; where one may get the second, I know not, but the want of it is accountable for more failures in the foreign field than anything else; and the third, although invaluable, can only be right as the outcome of the former. To spend years among the Ngoni and be denied many liberties may, indeed, be an undignified position for a free-born Briton ; but mere questions of dignity ought not to trouble the slaves of Christ in the work to which they have been called. Little by little, as we shall see, our position was improved among the Ngoni, and the years of apparent unfruitfulness were necessary preparation for the intelligent acceptance of the Gospel.

Sunday, November 15, 2015

27

Sunday, November 15, 2015

Samuel Albert

Read more...

IZITHAKAZELO OF NGUNI CLANS

Below are some izithakazelo (Kinship group praises) for some nguni or ngoni clans collected from the web. As you may notice some are in Zulu, Xhosa and other nguni languages. You can use http://www.isizulu.net to get the meaning of the words. This site has an online zulu dictionary that you may also use to translate the ngoni songs found on this site. Remember that isiZulu, isiNgoni, isiXhosa, siSwati and isindebele are all nguni languages and are therefore mutually intelligible.

Note: Isithakazelo (plural Izithakazelo)are poems praising important people e.g. ancestors within a Nguni clan. They are the story of a clan. The shortened version is used as a fond greeting of a clan member.

Zithakazelo zakwaMsimang (now known as Simango in Malawi according to GT Nurse)

Thabizolo

Nonkosi

Mhlehlela

Nhlokozabafo

Sdindi Kasiphuki

Sihlula amadoda

Mphand`umnkenkenke

Mlotshwa...

Zithakazelo zakwa Khumalo

Mntungwa!

Mbulaz'omnyama

Abathi bedla, umuntu bebe bemyenga ngendaba.

Abadl'izimf'ezimbili Ikhambi laphuma lilinye.

Lobengula kaMzilikazi, Mzilikazi kaMashobana

Shobana noGasa kaZikode, Zikode kaMkhatshwa.

Mabaso owabas'entabeni, Kwadliwa ilanga lishona

Bantungw'abancwaba!

Zindlovu ezibantu, Zindlovu ezimacocombela.

Nina bakwaMawela, Owawel'iZambezi ngezikhali.

Nina bakaNkomo zavul'inqaba, Zavul'inqaba ngezimpondo kwelaseNgome.

Nina enal'ukudl'umlenze KwaBulawayo!

Mantungw'amahle! Bantwana benkosi, Nina bakwaNtokela!

Ndabezitha!

Maqhaw'amakhulu

Izithakazelo zakwa-Dlamini (Nkosi)

Nkosi

Dlamini Hlubi

Ludonga LaMavuso

Abay`embo bebuyelela

Sidwaba sikaLuthuli

Wena esingangcwaba sibuye noMlandakazi

Abawela lubombo ngekuhlehletela

Nina baSobhuza uSomhlolo

Umsazi kaSobhuza

Mlangeni

Nina bakwakusa neLanga

Nina bakwaWawawa

Lokothwana

Sibalukhulu

Nina beNgwane

Nina besicoco sangenhlana

Nina beKunene

ezakwa Khambule

Mncube!

Mzilankatha!

Nina bakwaNkomo zilal'uwaca

Ezamadojeyana zilal'amankengana

Mlotshwa!

Malandel'ilanga

Mpangazitha!

Magosolo!

Nina basebuhlen'obungangcakazi

Abadl'umbilini wenkomo kungafanele

Kwakufanel'udliwe ngabalandakazi

Nina bakaDambuza Mthabathe

Nina basemaNcubeni

Enabalekel'uShaka

Naziphons'emfuleni

Kwakhuz'abantu banifihla

Naphenduk'abakwaKhambule

Nafik'eSwazini

Naphenduk'uNkambule

Nina baseSilutshana

Nin'enakhelana noMbunda

Nina bakaMaweni

'Thina bakwa Mhlongo sithi'

Makhedama!

Soyengwase!

Nina bakaBhebhe kaMthendeka

Nina bakaSoqubele onjengegundane

Nina baseSiweni

KwaMpuku yakwaMselemusi

KwaNogwence webaya

Zingwazi zempi yakwaNdunu

Njoman'eyaduk'iminyakanyaka

Yatholakal'onyakeni wesine

Yabuye yatholakala ngowesikhombisa

Langeni

Owavel'elangeni.

Ngaphandle ke uma ngingatshelwanga kahle ekhaya.

Izithakazelo zakwa-Ndlovu.

Gatsheni!

Boya benyathi!

Buyasongwa buyasombuluka.

Mpongo kaZingelwayo!

Nina bakwandlovu zidl' ekhaya,

Ngokweswel' abelusi.

Nina bakwakhumbula amagwala.

Nina bakwademazane ntombazana

Nina bakwasihlangu sihle.

Mthiyane!

Ngokuthiy'amadod'emazibukweni.

Nina bakwaMdubusi!

Izithakazelo Zakwa-gumede

Mnguni! Qwabe!

Mnguni kaYeyeye

osidlabehlezi

BakaKhondlo kaPhakathwayo

Abathi bedla, babeyenga umuntu ngendaba

Abathi "dluya kubeyethwe."

Kanti bahlinza imbuzi.

Bathi umlobokazi ubeyethe kayikhuni

Sidika lolodaba!

Phakathwayo!

Wena kaMalandela

Ngokulandel' izinkomo zamadoda,

Amazala-nkosi lana!

Mpangazitha!

Izithakazelo zakwaMabaso

Mntungwa,

Ndabezitha,

Mbulazi ,

wen' odl' umunt' umyenga ngendaba,

wen' omanz' akhuphuk' intaba

Zithakazelo zakwaNgwenya

Ngwenya(South African version)

Mntimande,

Bambolunye,

zingaba mbili,

zifuze konina,

ekhabonina,

mabuya,

bengasabuyi

baye babuya

emangwaneni ,

nungunde,

wakhothe,

bayosala beziloyanisa

Zithakazelo zakwaZulu

Zulu kaMalandela;

Zulu omnyama ondlela zimhlophe.

Nina baka Phunga no Mageba.

Ndaba; nina bakaMjokwane kaNdaba.

Nina benkayishana kaMenzi eyaphunga umlaza ngameva.

Mnguni, Gumede.

Ndabezitha

Izithakazelo zakwa zungu:

Gwabini,

manzini,

geda,

nyama kayishe eshaya ngamaphephezeli

ncwane,

hamashe,

geda,

wena owaphuma ngenoni emgodini,

wena owakithi le emaheyeni,sengwayo

I have just noted that some people have been trying to search for the meaning of the word ndabezitha used above and in some Zulu films such as Shaka Zulu below.

Ndabezitha is the one of the praise and respect words used when the Zulus and other Ngunis want to acknowledge loyalty to a Nguni royalty. Just as in English one would say, 'your majesty or his royal majesty or your royal majesty' to their king, in Zulu and other nguni words you use the praise word ndabezitha. The word is a contraction of indaba yezitha literally meaning 'matter of the enemies'

Sunday, March 11, 2012

0

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Samuel Albert

The succession to the Paramountcy and the role of the regent

Mtwalo said to Mbelwa 'You are the right man to be inkosi. I am not the right man because through jealousy Ntabeni gave the inkosi to Mpeseni.' Then they gave Bayete' to Mbelwa."

Footnotes

Read more...

Ngoni Paramountcy Part 1

by Margaret Read.

THE Chewa term for chief (mfumu) was widely used in Nyasaland for chiefs of all ranks, as well as for village headmen and, occasionally, as an honorific form of address to an important individual. Among the Cewa a man could 'become a chief' by acquiring, through marriage or purchase, the right to own a site, known as a mzinda, on which female initiation rites were carried out. This concept of the office of chieftainship among the Cewa and other local tribes was in sharp contrast to the centralized and unified concept inherent in the Ngoni term inkosi. I have translated inkosi here as Paramount because the term Paramount Chief was adopted by the Administration to denote a ruler who had recognized subordinate chiefs under him and whose court was an appeal court for their courts. It is necessary to emphasize here how distinctive the office of Paramount was among the various types of chiefs in Nyasaland, both in official recognition, and still more in the Ngoni ideas about their Paramount. We saw in Chapter II of Part I that no Nyasaland chiefs, except the Ngoni Paramounts, had Subordinate Native Authorities under them.

When the Ngoni left the south, a number of small chiefdoms there were gradually being overcome by Shaka and, based on his armies, he had set up a new and unique type of inkosi. The leaders of military bands who left him Mzilikazi, Soshangane, Zwangendaba and Ngwana—had little recognition before they left, except as military and clan leaders. Yet after the Ngoni left, Zwangendaba and Ngwana received from their followers recognition of their political leadership as inkosi, and this was expressed by giving to the Paramount the salute of Bayete. Throughout their recitals of traditions and in their accounts of their political system, Ngoni informants in both kingdoms emphasized that for each kingdom there was one inkosi to whom alone the Bayete was given. We assume, therefore, that the later Ngoni concept of the Paramount and his function and authority was largely evolved and built up during the Ngoni migration across the Zambesi and the early settlement in Nyasaland.

The office of the Paramount was supported by three typical Ngoni institutions. The first was the regency exercised by the man who was held responsible for the care of the office of the Paramount. He was called 'the one who takes care of the country', 'the one who has to put the new inkosi in his place', 'the one who takes care of the young inkosi until he enters his father's place'. We shall see later how this principle of regency operated in particular cases in the succession to the Paramountcy. It proved to be an effective provision both in the case of a minor who was recognized as his father's heir, and during an interregnum while the succession was being discussed. The Ngoni showed a clear understanding of what functions the regent ought to perform, and when he exceeded these functions and usurped, or tried to usurp, the Paramount's position they condemned his action as wrong.

The second institution which supported the Paramountcy was the `big house' from which the heir to the Paramount had to come. We shall see later that it was not always considered essential that the heir should be the actual child of the wife in the big house. A boy could be adopted into the house and, by Ngoni kinship rules, he was then a child of that house and of the woman in it.

The third institution, which made the Paramount immortal at death after having been supreme in his life-time, was the Ngoni practice of `guarding his spirit' in a hut, usually in the village where he had lived. The guardianship of a spirit was not practised exclusively for the Paramount. All the chiefs and the heads of the Swazi clans had this provision made for their spirits when they died, but in national crises prayers addressed to the spirits of former Paramounts were of supreme importance.

The royal clan and the big house

Among the Swazi and trans-Zambesi clans which formed the Ngoni aristocracy the royal clan had a unique position. Not only was it the clan of the Paramount, but its members had social rank and prestige because they belonged to his clan. In the northern kingdom informants showed awareness of the fact that their royal clan of Jere was not one of the well-known clans in the south. Other clan names found among them, such as Ngomezulu, Thole, Nzima, Nqumayo, and many more, were known to be clan names among the South-eastern Bantu. The following explanation was given by Cibambo about the name Jere and was the one most widely accepted:

The Ngoni themselves say that the clan name of Jere was given during the journey, and that it arose out of the number of people who were with Zwangendaba. When the Ngoni want to speak of a large number of people they use two well-known words which are: `Ngu Shaka' (it is Shaka); 'Ngu Jere' (it is Jere). Perhaps Zwangendaba and others took their clan name from this, seeing that they had become a great number. It is certain that the clan name of Jere is not known in Zululand or Swaziland

In the northern kingdom all the chiefs recognized as Subordinate Native Authorities were of the royal clan, and hence its political authority was widespread. It was noticed by the early missionaries in northern Ngoniland that the sons of Zwangendaba who were chiefs under their brother, the Paramount, showed some degree of independence in that they wanted to rule their own areas with the minimum of centralized control. The pre-eminence of the Paramount among the other Jere rulers was strengthened as time went on by the remoter kinship relationship of the other Jere chiefs to the Paramount. After Zwangendaba's death they were his brothers of the same father and different mothers. Two generations later they were farther removed from his kinship circle since each of their posts was inherited on a direct father to son principle. The political and social importance of membership of the royal clan tended to go in the direct line of relationship to the Paramount rather than to the collateral branches. Later, in Part III, we shall examine the social prestige of the amakosana (lit. children of the inkosi). It was the closeness of their relationship to the reigning Paramount which was the basis for their social prestige, though evidence showed that a sister or brother or child from a big house of a former Paramount was also given social recognition as an important personage.

The royal clan of Maseko in the central kingdom was also known in Swaziland. Dr. Kuper refers to it in connexion with the Swazi custom of cremating the body of the Maseko chief at his death on a rock by a river.(See Kuper, H. An African Aristocracy, p. 86.) This custom was brought from the south by the Ngoni under Maseko leadership and carried out for each successive Paramount up to 1891. Among these Ngoni the royal clan had special relationships with other leading clans, but the Paramount did not share his political authority with any others of his clan. His chiefs were all of other clans, and Ngoni informants said that it was a deliberate act of the Paramount Mputa to exclude his brothers from political authority and from disputing with him the control of the kingdom. In the isolated position thus established for the royal clan, two other clans had a ritual relationship with the Paramount. One was the Phungwako clan which was custodian of the Paramount's 'medicines', known as the tonga. The other was the Ngozo clan which provided the companion for the Paramount whom I have called the 'royal shadow' (see below, pp. 61-3). Yet another special relationship with the royal clan was that of the Nzunga clan which had chibale, or brotherly relations, with the Maseko clan, that involved sharing the same avoidances and excluded inter-marriage.

The relationship of the Paramount to other leaders of the royal clan was thus different in the two kingdoms. In the north he was one ruler, though a supreme one, among several ruling kinsmen of the same clan. His position in the past had been strengthened by the prestige shared by his clansmen, but also challenged by his near kinsmen in positions of authority. In the central kingdom the Paramount shared no authority with his fellow clansmen. He was unique among them as a ruler, while sharing special ritual relationships with the two other clans which supported his position without challenging it.

A new Paramount, in order to be installed in his father's place, had to be of the big house as well as of the royal clan. Dr. Kuper described the Swazi practice whereby cattle were contributed by the nation for the mother of the king, so that she was called the 'mother of the people of the country'. She also described the ritual marriage of the first wife of a ruler, who was called sisulamsiti , and who was never the mother of the heir.(See Kuper, H. op. cit. pp. 54 & 91) The Ngoni Paramount-elect in the northern kingdom married his first wife when he was a young man and she was called msulamsizi, 'the one who takes the darkness off him'. The big wife, who would bear the heir, was married with a large gift of cattle taken from the herd of the big wife of the reigning Paramount and, after marriage, was attached to her big house. We shall discuss in greater detail in the next chapter the relationships of the royal women to the Paramount and to each other. Here it is important to note that the big house owned by the big wife was the place where the future chief was brought up. In the central kingdom the first marriage of the Paramount was traditionally with a woman of the Magagula clan who was said not to bear children. She held an honoured place in the social hierarchy and was married with cattle taken from the herd of the gogo house of the reigning Paramount. It was regarded as a ritual marriage, for if she did bear children they were not acknowledged. Informants were uncertain whether methods to prevent conception were used, or whether abortion was practised, or whether children, if born, died young or were disposed of or placed out in other households. The last alternatives were unlikely, and one of the first two expedients was in line with the phrase always used of this wife: 'she did not bear children'. The wife who bore the heir was married next and was always of another leading clan, and the cattle for her came from the herd of the big house of the reigning Paramount.

The reasons were obvious why the remembered genealogies of the Ngoni Paramounts of the royal clans were short compared with the genealogies of some other African royal houses. The remote ancestors of Jere chiefs and Maseko chiefs, who were, as we have seen, not Paramounts before they left the south, were forgotten once the departure had taken place. Only a few names had been handed down and were repeated by the official praisers, whose task it was to call out the names of the direct ancestors of the Paramount before declaiming his izibongo or praise-songs. The northern Ngoni remembered the names of five direct ancestors of Zwangendaba, ancestors who had died before they left the south, and the central Ngoni remembered the names of three direct ancestors of Mputa who had died before crossing the Zambesi.'

The genealogy of the Jere Paramounts which was recited in the northern kingdom varied in different localities. Of three versions which I found two agreed, except in the name given for the earliest ancestor.

Lovuma (Kali is the alternative given by Cibambo)

Lonyanda

Magalera Died in the south

Magangata

Hlacwayo

Zwangandaba

Mbelwa I

Mbelwa II

Mbelwa III, ruling in 1939

The list above was given by Cibambo of Ekwendeni and Simon Nhlane of Hoho, the leading member of the Nhlane clan.

Third Version: Nyandeni

Mehlo enzhomo

Jele ka Lovuma

Nchingile

Gumede

Magangata

Hlacwayo

Zwangendaba

Mbelwa I

Mbelwa II

Mbelwa III

1 In 'Traditions and Prestige among the Ngoni' (Africa, 1936) I said (p. 466) that nine generations of ancestors were remembered in the north and seven in the centre. These referred to the Paramounts after crossing the Zambesi as well as to their ancestors who died in the south.

The third version was given by Chinombo Jere, a grandson of Zwangendaba, who came from Emcisweni. This section of the Ngoni, under Chief Mperembe, had for a time associated with Paramount Mpeseni, and not with Mbelwa. This separation gave them a slightly different set of traditions, and they were, perhaps owing to their geographical isolation, the last group to give up the old language and dress.

An attempt to check the Emcisweni version of the Jere genealogy with that of Ekwendeni showed one piece of evidence in favour of the latter. This was the tradition preserved by the Nhlane clan that the Swazi chiefs of the Nqumayo clan had as their chief izinduna men of the Jere clan who were of the same age regiment. The names remembered were as follows:

| Swazi Chiefs | Ngoni Izinduna |

| Ndwandwe | Magalela |

| Langa | Magangata |

| Zwide | Hlacwayo |

| Sikunyane | Zwangendaba |

In the central Ngoni kingdom the following was the generally accepted version of the genealogy of the Maseko Paramounts:

Msizi no bulako Died in the south

Goqweni Died in the South

Ngwana Died before crossing the Zambesi

Mputa

Chikusi

Gomani I

Gomani II, ruling in 1939

After the death of Ngwana before the crossing of the Zambesi, two of his brothers in turn acted as regents. Also, on the death of Mputa, his brother Cidyawonga acted as regent. In the recital of the Paramount's genealogies, however, the names of the regents were not included.

The succession to the Paramountcy and the role of the regent

It might appear that among a strictly patrilineal people like the Ngoni, where marriage was formalized by exchange of cattle, and where each wife had a recognized position and rank, it would have been easy to formulate rules for the succession to the Paramountcy, and that they would have been followed without deviation. Such had obviously not been the case. It could be argued that the unsettled conditions on the northward journey made it necessary to modify rules of succession in favour of the 'strong man'. Europeans have tried to detect an element of popular choice in the appointment of the inkosi, or at least of a popular verdict in favour of or against a proposed candidate. Another element suggested by Ngoni informants was nomination of his heir by the dying Paramount.

There were, however, certain principles which were clear in the accounts given by informants. One was that immediately on the death of a Paramount a regent took charge of the country, of the office of the Paramount, and of the person of the heir elect, and also of the funeral rites of the dead Paramount. The provision for a regency allowed for a period of delay before announcing the successor. There was no 'The king is dead. Long live the king.' The office of the Paramount was clearly in suspense during this interregnum which had been known to last a few days, a few months, or even years—the last in the case of a successor who was a minor. During this period the regent was responsible for carrying on the work of the Paramount, and for consultation with heads of leading clans about the successor. In the past the regent was usually a brother of the dead Paramount. The traditions of the central Ngoni were, as we have seen, that after Ngwana had led them out of the south, he died before crossing the Zambesi. Two of his brothers, Magadlera who died before the Zambesi crossing and Mgoola who died near Domwe, successively acted as regents until Mputa was old enough to enter his father's place. When the time came for the end of the interregnum, it was the regent's responsibility to summon the people and present the heir to them as the new Paramount.

The assumption of authority by a regent and the provision for an interregnum make it clear that the identity of the successor was seldom a foregone conclusion even though the heir-apparent stood with a spear at his father's grave. Among the principles of succession which determined the choice of the new Paramount, one was that he should come from the big house. This could be 'arranged' by adopting him into it if there was no likely heir who had been born there. Another principle was a less easily defined qualification, that of suitability. This was discussed by the regent with the leading clan heads, who took into account the wishes of the late Paramount and the character and personality already displayed by the proposed successor, who had stood by his father's grave. Informants made it clear that responsibility for this selection weighed heavily on the regent and the leading men, for the choice once made was final, the power of the Paramount was very great, the 'medicines' used at his accession 'set him aside as a person of potential supernatural power, and the prosperity of the country and of everyone in it depended on this decision.

Two famous cases of disputed succession in the past had led to major divisions of the Ngoni kingdoms. The first occurred in the north on the death of Zwangendaba, when his brother Ntabeni became regent, and this dispute revolved round the principle that the heir should come from the big house. It led to the final split between Mpezeni and Mbelwa, the setting up of two kingdoms, and the giving of the Bayete' to two Paramounts of the Jere clan. The following account was given by Chief Mtwalo Jere, son of the Mtwalo mentioned, and he told it to me in his own village of Ezondweni. It brings out the function and position of the regent; the relation of 'house' to `village'; the influence of the popular verdict on the choice of a successor; the magnanimous attitude of other possible rivals for the Paramountcy; and the effect of personal quarrels on a national matter.

"Ntabeni went to the house of Munene, the mother of Mbelwa. She insulted him and would not give him beer. Zwangendaba went to bathe and when he returned Ntabeni said to him 'I have been insulted by your wife. She called me "Sutu".' This is a great insult among the Ngoni.1 Zwangendaba was very angry, and he took a pan and fried groundnuts, and said to his wife 'You must take the groundnuts in your hand.' Her hands were very burnt because the groundnuts were too hot. 'You are burnt because you must not abuse this your brother-in-law. You are punished.' Zwangendaba died. Ntabeni was taking care of the country. He was the right man to put the inkosi. He said to Mbelwa: 'You are not a chief because your mother abused me.' So Mpeseni was inkosi, and the second was Mtwalo. They chased away Mbelwa. When Mpeseni was elected to be inkosi all the people were complaining because they said the chieftainship should be for the village of Elangeni. The people of Elangeni and of Ekwendeni did not want Mpeseni as inkosi.

Ntabeni died. The people of Elangeni and of Ekwendeni wanted to fight Ntabeni's people because they were not told of his death, and when he was buried they were not there. The Ntabeni people went away to Tanganyika. All the rest left Ufipa and came to Cidlodlo. Mpeseni and Mperembe stayed there and the rest came to Coma. Then Mperembe returned from Mpeseni.

Mtwalo said to Mbelwa 'You are the right man to be inkosi. I am not the right man because through jealousy Ntabeni gave the inkosi to Mpeseni.' Then they gave Bayete' to Mbelwa."

Cibambo, whose father was mlomo wenkosi (mouthpiece of the chief) in Ekwendeni for old Mtwalo mentioned above, confirmed this part of the story of the succession and the role played by Ntabeni as regent. He also gave in his book 2 the most coherent account of an earlier dispute about which wife of Zwangendaba was the big wife—a dispute which illustrated the significance of the house in the succession.

A disputed succession in the central kingdom arose over a struggle between Chikusi, the son of the Paramount Mputa, and Cifisi, the son of the regent Cidyawonga who took care of the kingdom after Mputa's death. When the regent died, his son Cifisi claimed the succession and war broke out between the followers of the two claimants. After fighting had continued through two generations of claimants the state under Cifisi seceded and became independent, though the `Bayete' was only given to Cikusi and his descendants of Mputa's main line. The following account was given in the royal village of the central kingdom by a former regent assisted by an official reciter of tradition. It related to the succession to Mputa, who died in the Songea district of Tanganyika, and to the defeat of these Ngoni by the followers of Zulu Gama. After this defeat the Ngoni under Cidyawonga returned to the west side of the lake and built on Domwe mountain.

"When they burned the body of Mputa, Chidyawonga stood with Chikusi, and that was the sign that Cikusi was still young but was inkosi. Cidyawonga was the brother of Mputa. The people told Cidyawonga 'We are in war. You must help us.' They took Chikusi and put him in the big house, because there were no children there.

Chidyawonga was the regent when they built on Domwe. When he was about to die he said to the people 'Now I leave this country in the hands of the owner, because I was only appointed to keep it for him. This is your leader.' He sent for Cikusi and gave him his father's spear, saying to him `This country is yours.' He said to Cifisi, his own son, ' You my son do not struggle with Cikusi. He is the only Paramount here.' Cidyawonga we did not burn because he had cared for the Paramountcy. And when Cidyawonga died we put Cikusi in his place."

The relation between the regent and the Paramount emerged again from the confusion following the death of Paramount Gomani I in 1896 at the hands of the British. The record in the Ncheu District Note Book said that authority was divided between the dead Paramount's brother, Mandala, and NaMlangeni, the mother of Chikusi the former Paramount. After the Portuguese-Nyasaland boundary was fixed dividing the Ngoni territory, the Portuguese entered their section to administer it. NaMlangeni and Mandala resisted their entry and were taken prisoners and died. Meantime a big mulumuzana of Paramount Gomani I had acted as regent for his heir who had been placed in the big house. The following account by the treasurer of Gomani II described the situation during the early years of the minority of the Paramount.

"Chief Gomani II was born in 1893. The country was destroyed by the Europeans when this child was three years old, and he was taken care of by the big mulumuzana of his father, Cakumbira Mpalale Ndau. When the war of the Europeans had finished, they built the village of Lizulu, near Mlanda mountain, where the Dutch mission is today. The child was with them in that village.

When the European Mr. Walker asked the big people whether Gomani I left any children, those big people refused to tell and said 'He did not leave children, they died when they were small.' They feared lest perhaps the Europeans wanted to kill the children too. Mr. Walker (they called him Chipyoza, 'the thing that goes on boring a hole') did not stop asking because he said `Gomani was my friend and I want to help his children.' On his second journey they revealed to him that there were two children in the village here, and they named the heir Philip Gomani and his younger brother William Gomani who died in 1919. Then Mr. Walker rejoiced. When they brought the children out before his eyes, he gave them gifts which he brought for them, clothes and other things."

Footnotes

1. Bryant, in Olden Times in Zululand and Natal, said (p. 134) that `Sutu' was an insult because it meant 'harharian'—one who had not had his ears pierced according to the custom of the Zulu.

2.Cibambo, Y. M. My Ngoni of Nyasaland. London, 1942, chaps. V & VI.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)